Shuggie Otis – Pling! / Maestro Rhythm King

»Just to find the kind /

Shuggie Otis, »Happy House«, LP Inspiration Information, CBS Records 1974.

of another time /

down the road a bit /

I’ve been walking it«

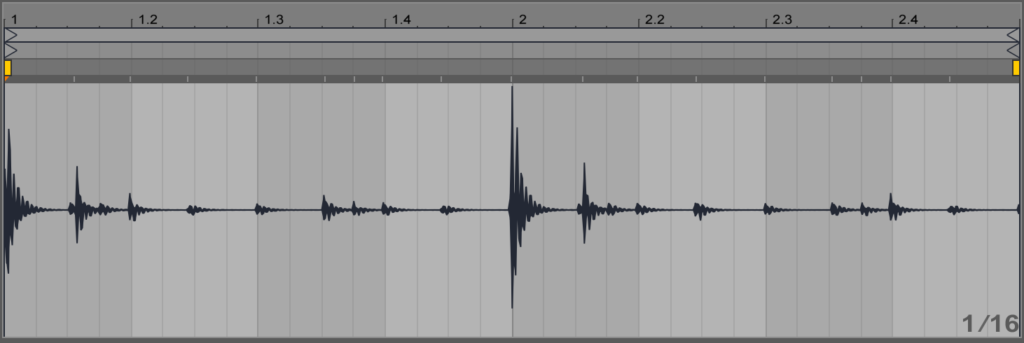

The needle slowly slides into the groove. It clatters. The penultimate track of the B-side has been played many times. You can hear that clearly. Each play-through has left its subtle electrostatic traces. Without warning, a drum pattern starts in the middle of the crackling carpet. Just like that, as if everything had been going on for a while, the track starts on the 3-and of a slow 6/8 figure. Kick and snare drum mark the quarter notes for the sake of order; beats 2 and 3 are filled by toms and maracas with strangely straight sixteenth notes, and through it all prances an echoing clave figure played on a stick. You shouldn’t take kick, snare, stick too literally, though, because this doesn’t have much to do with a classic drum set any more. The drums on Shuggie Otis’ “Pling!” from his 1974 album Inspiration Information are not drums at all. There are no skins or woods vibrating here, but oscillators. And this 6/8 pattern in its almost hypnotic slowness is not the result of psychedelic deceleration of human drumming, but simply the tempo control of a Rhythm King drum machine by Maestro turned to minimum stop.

After the Rhythm King has trotted along largely on its own for two bars, an electric piano played in a low register only hesitantly joins in. It circles around a few floating seventh chords, at first only hinting at them with a few notes, then filling them out more and more, winding its way up a bit via a second part, finally returning to a variation of the first and fanning it out across the entire width of the keyboard. Like mist, the electric piano spreads out above the drum pattern, gradually unfolding a sonic space that – paradoxically – becomes narrower with each further opening. Even the first, low notes are of a barely permeable density. Beats and tremolos make them tumble and gradually waft into every free gap of the frequency spectrum. A second time through the B-part. It gets tighter and tighter. The air gets cut off. At 1:28 someone has to cough. Shortly afterwards, with the return to the main section, this shimmering electric piano bubble bursts like a punctured balloon – ›Pling!‹ – and disperses gaseously between shimmering harps and drawn-out strings of horns. But the game starts all over again. Tightness – expansion – and then, at just under three minutes, final discharge. Airy choirs and glockenspiel, organ and speckles of harp swirl in all directions, interspersed with a saxophone that only belatedly gives it all a theme. After more than four minutes, the fog of sound gently fades. Only the Rhythm King continues his rounds undeterred, and perhaps only now do we realise that he was there the whole time. Fade out …

What does this »Pling!« aspire to be? The above description sounds pretty traditional behind the standard sonic fiction rhetoric. Building up tension and finally resolving it, as if music history simply couldn’t think of anything better. But it’s no longer really about the pathetic cadencing of human emotional turmoil. It’s more about a kind of Fender Rhodes/Rhythm King experimental system that explores the dynamics of sonic aggregate states. Above all, however, »Pling!« is not a pop song (– although the division into A and B parts and the quasi-chorus does its best to keep up appearances). Rather, Shuggie Otis designs a prototypical version of track music, as it will be described later by Jochen Bonz and Johannes Ismaiel-Wendt. And that also means: he drafts a different organisation of musical time.

Shuggie Otis has turned the tempo control of his Rhythm King way down to have enough time to play with just that. The funkbox runs in slow motion, spreading the slopes of its clock pulse as wide as possible to let the electric piano slowly seep into it. At the same time, this almost exaggerated slowness allows the different rhythmic levels of the rhythm pattern to wash over each other in undulating motion. Sometimes the sixteenth-note rumble of toms and maracas spills upwards, then it is covered again by the echoing clave, before finally the backbeat of kick and snare crashes over it, foaming up a spray of 6/8 hi hats.

Shuggie Otis’s approach to the Rhythm King is engineering, but no longer in the sense of a technicist foundation of musical practice in axiomatic laws, as we found it conceived by Joseph Schillinger or Raymond Scott. Rather, it is genuinely sensory engineering, in the sense of Kodwo Eshun via Rolf Großmann:

»›[S]ensory engineering‹ (with Kodwo Eshun) is an open, experimental and dynamic practical knowledge of direct affection (Affizierung). […] [It generates] a new epistemic situation: the knowledge of designing the rhythmic ›feel‹ of a song or track; its ›swing‹, ›off-beat‹ and ›groove‹ diffuses into the mechanical grid of technical equipment and its control.«

Großmann, Rolf (2014): »Sensory Engineering. Affects and the Mechanics of Musical Time«. In: Marie-Luise Angerer/Bernd Bösel/Michaela Ott (Hg.): Timing of Affect. Epistemologies, Aesthetics, Politics. Zürich: diaphanes. S. 191-205. Hier: S. 192.

In this new epistemic condition that Großmann describes here, a specific rhythmic knowledge – a knowledge of ›fee‹ and ›groove‹ – has seeped into technical things, like Shuggie Otis’ electric piano chords into the pattern of the Rhythm King. Sensory engineering allows the technicality of all aesthetic practice and the aestheticity of all technical processes to become describable in their inevitable interlocking. As said, it can then no longer be a matter of strict axiomatics (the cliché of engineering science), but of taking seriously the manifold and diverse – technical, aesthetic, cultural, … – forms of knowledge and taking them into account in research. Sensory engineering is techno-aesthetic tinkering. The rhythm pattern is an epistemological seepage.

Shuggie Otis’s approach to the Rhythm King is funk – precisely in Tony Bolden’s sense of a specific »kinetic epistemology«. The groove of the machine is wrung out in all its slowness, the beats are stretched until just before they shatter, in order to experimentally find out how far this can be pushed, how long the »feel« of this groove holds together. Such questions, however, can only be explored sensorily per se. Later on, I will go into this in more detail using Tiger C. Roholt’s concept of groove. First let it suffice to note that funk as ›kinetic epistemology‹ traces precisely that diffuse, infiltrated rhythmic knowledge that Großmann also describes. A rhythmic knowledge, in other words, that revolves precisely around ambiguities and amalgamations and allows them to revolve without wanting to resolve them. Sensory engineering, techno-aesthetic tinkering, is much more complex than a well-ordered algorithmic musical construction kit. And I already suspect that this hypnotically slow pattern from Shuggie Otis is so funky precisely because it remains ambiguous, is not itself a unity, but an interlocking, an interplay, a combination.

I switch on the Rhythm King. That’s a bit exciting every time, because something might have gone broken since the last time it ran. But everything still seems to be working. A mains hum can be heard, maybe it’s the transformer. So I select a pattern, tap the connected pedal and the Rhythm King starts to play. Much too fast, the tempo is somewhere around 100 BPM. To find out what settings Shuggie Otis used on »Pling!«, I turn the tempo control back further and further. But even that is not enough. At just under 70 BPM, it’s still much faster than the track, which itself runs at a leisurely 56 BPM.

Shuggie Otis must have recorded a rhythm track and then reduced the tape speed. Hence the somewhat duller and more pressing sound, especially of the snare. The sound in general: On the record it sounds as if the Rhythm King was first sent through a guitar amp or something like that and then miked. I haven’t found the pattern used yet either. The »Slow Rock« runs appropriately on 6/8 with kick and snare drum on the quarters. But that’s not all that happens with Shuggie Otis.

I click through the presets bit by bit, but nothing matches the drums on the recording. Only when I hold down the »Slow Rock« button and also select »Rumba« does everything suddenly fit together. Because the Slow Rock makes the Rhythm King’s time-point generator pulse in 6/8, the 4/4 rumba suddenly works very differently. That’s why it never seemed possible to assemble the »Pling!« pattern from audio loops of the Rhythm King presets. Two presets pressed together do not simply add up, they create a new interconnection of the logic matrix, a ›third‹ (in Michel Serres’ sense) pulse pattern. So once again: machinic heterochronicity. I release the two pressed buttons. Now only the time-point generator continues to run and the pulse pattern can be clearly heard on the output. Now, is this ›[techno-]sonic tempor(e)ality‹ in and of itself? I don’t know, but let the machine run a little longer. Keep that funky groove going …

This Listening Session is a translation from the book ›Futurhythmaschinen‹. Drum-Machines und die Zukünfte auditiver Kulturen by Malte Pelleter. The book (in german language) can be accessed here.

Citation: Pelleter, Malte (2020): ›Futurhythmaschinen‹. Drum-Machines und die Zukünfte auditiver Kulturen. Hildesheim: Olms und Universitätsverlag. 239-243.