The Aliasing of the SP-1200

I would like to take a closer listen to this clanking SP-1200 sound myself. In order to ensure a supposedly unbiased access to the sound characteristics of the machine, I first create a sine sweep in a common audio editing software – a simple sine tone that sweeps the frequency range from 0 to 20 kHz from bottom to top in two seconds. Right across the human auditory spectrum. David Yeh did something similar for his circuit modeling project, and it makes sense that a sweep of this kind makes aliasing frequencies immediately audible.

So I sample the sweep in the SP-1200. The length of two seconds is chosen so that it does not exceed the maximum of 2.5 seconds. When I play the sample on the first pad, I don’t hear anything remarkable at first. The sine tone still hisses largely undisturbed up to the upper frequency range. However, it is clearly noticeable that it does not make it quite as far as the original sound that I had sampled. The sample rate of the machine is, as already described, 26.04 kHz. So the sweep runs well beyond the corresponding Nyquist limit, which in this case is 13.02 kHz. However, as Yeh’s description already suggested, the anti-aliasing filter at the SP-1200’s sample input seems to do its job relatively well, preventing the frequencies that cannot be digitized correctly from passing through in the first place.

Listening to the sampled sweep again, this time with headphones. When the frequency arrives in the upper range, I hear a kind of chirping that flashes only minimally briefly just before the sound disappears. Compared to the original sound, the difference is quite noticeable, but remains subtle all in all.

Then I switch to the tuning mode of the SP. Now I can detune the samples in semitone steps using the faders. A total of sixteen steps are possible, seven upwards, the basic tuning, eight downwards. I tune my sweep down by just one semitone, trigger it again on the pad – and what was once a single sine tone has suddenly multiplied into a whole series of tones. The original sweep is still clearly discernible, but now sounds distorted and scratchy. Most importantly, a second siren-like tone has been added, whose frequency doesn’t stay the same or run in one direction like the sweep, but swings up and down as if modulated by an LFO. I tune the sample down another step and the sound changes once again. Again, the scratchy sweep is supplemented by a kind of siren, but this time it oscillates much more slowly. At the tuning of three semitones down, it speeds up again, and now several fast sirens flicker on top of each other. Finally, at four semitones, the sweep itself seems to be frequency modulated. A distorting shimmering is added to the treble band. Five steps sound less distorted, six even more so. At seven semitones, I hear the sine tone sink again at the end and disappear into sizzling noise. At eight semitones, it is again surrounded by several frequency-modulated tones and can hardly be distinguished from them any longer.

There is something strangely fascinating about tuning these test tones up and down in the machine. Hearing them this way, it becomes quite comprehensible what makes up the specific sound of the SP-1200. Here, the signal processing generates massive new signal components, obviously complex frequency patterns that radically color the sound. At the same time, however, it is equally clear that I will not be able to grasp this very sound of the SP itself, which is appreciated and celebrated by so many producers, on the basis of this trickery of test tones.

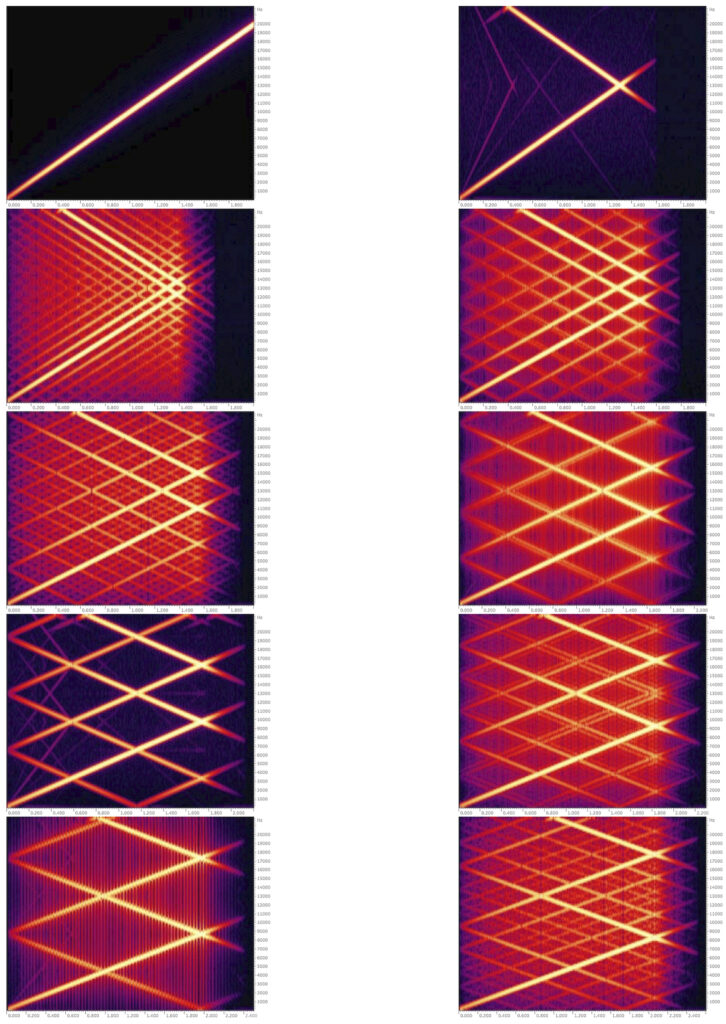

But before I try another sample source, I want to take a closer look at these aliasing patterns using the detuned sweeps. To do this, I record the different tunings in the computer and display spectograms for them. These show exactly what I have just vaguely described as an auditory impression: Already with the sweep in the original tuning an aliasing frequency is clearly recognizable, which results from the reflection of the rising sine tone at the Nyquist limit. In the sample itself it was barely audible. The brief chirp I noticed probably marks the crossing of the two frequencies and the descent of the aliasing frequency into the audible range. The other recordings of the tuned-down sounds, however, show much more complex and, in each case, characteristic aliasing patterns. What I have just heard as frequency-modulated siren sounds becomes recognizable here as such pattern formation by manifold mirroring of the output frequency. The spectograms make immediately visible how much the energy is distributed differently in the frequency range compared to the once tidy output signal and how massively this aliasing via pitch shifting affects the character of the sound of the SP.

But again: Even the graphical orderliness of these aliasing patterns – which, by the way, would have been the mathematical delight of Joseph Schillinger – does not bring me closer to the legendary sound of the SP-1200. For that, more suitable sample material has to be chosen. I choose the piece »On The Hill« by saxophonist Oliver Sain. Not (only) because I find this piece so great in itself. But mainly because I know it was the sample source for »Day One«, a track by New York rap crew D.I.T.C. (short for Diggin’ In The Crates) that loops a wonderfully laid-back vibraphone flourish. And vibraphone samples just always sound good in the SP.

Soon I have found the sampled portion. However, the said loop, which plays the one in the beat of D.I.T.C., is not the beginning of the loop here, but stands right in the middle of it. In Ableton Live, I cut everything into the appropriate order and build the loop as I know it from the track. The looped two bars are almost six seconds long, so no chance for the SP-1200’s limited memory. But since I want to try out the pitch shifting anyway, this actually comes in handy. Similar to the common practice described above of speeding up the sample source on the turntable to squeeze more valuable seconds into the sample memory, I tune the sample up by six semitones in the software. The loop is now much faster. Once again divided into two pieces of one bar each, each is now just under two seconds long and I’m ready to go. I sample the two bars in the machine and then quickly sequence them back together as a loop. The tempo of the accelerated sample is now just under 119 BPM. Much too fast. Also, the sound impression is, as expected, still hardly changed in contrast to the source material in the computer. Next, I tune the sample down again by six semitones to bring it approximately to the original speed. The sound changes immediately.

Particularly the vibraphone notes now draw sugary trails of aliasing behind them along the loop. The bassline is more defined than in the source material, which is also due to the fact that the mono sampling of the machine has moved everything together in the center. The sound has clearly lost in transparency – or in positive terms: it has gained in density. The aliasing spreads thick and wide all over the sample, tugging at the mids and making the highs ring. The tempo is now 84 BPM. I pitch the sample up one step again, loop it and end up at about 89 BPM. This should be about the same tempo that D.I.T.C. used. The aliasing is much more subtle here, which fits in with the fact that you can see from the spectogram that the aliasing pattern is more reduced when tuning down five semitones compared to other tunings.

I tune the sample up and down for a while, try out different tempos and send it through the dynamic SSM2044 filter. But I always end up with the loop at the initial speed, let it run for a long time and nod my head to it, just as I should.

The aliasing as an intrinsic sound, a genuine Eigenklang, of the machine. The erstwhile noise has become a characteristic trait. This is exactly what can be heard in the SP-1200. The vibraphone loop from the sampler has been given a distinctly unique sound, which results precisely from the technical properties of the digital hardware. Its rudimentary signal processing colors the sound and thus becomes a genuinely techno-aesthetic dimension. A distinction between ‘technical’ and ‘aesthetic’ layers is no longer possible here. In the ringing aliasing, the two fold into each other.

Such aliasing in the SP-1200 is no longer a technical interference, but the becoming productive of digital ambiguity. Paradoxical reversal: digital sound, which is based precisely on the principle of the definite measurement and quantization of a signal for its subsequent reconstruction, takes a techno-aesthetic turn in that precisely the failure of this definite reconstruction is experienced aesthetically. From the gaps of the dropped sample values, an area of indeterminacy creeps back into the digital, which its supposed transparency actually wants to make forgotten. The sugary sound of the SP, however, suggests that the digital can also be ambiguous. And that this ambiguity sounds pretty good.

This Listening Session is a translation from the book ›Futurhythmaschinen‹. Drum-Machines und die Zukünfte auditiver Kulturen by Malte Pelleter. The book (in german language) can be accessed here.

Citation: Pelleter, Malte (2020): ›Futurhythmaschinen‹. Drum-Machines und die Zukünfte auditiver Kulturen. Hildesheim: Olms und Universitätsverlag. 517-520.